Bobby Sherman

The DeFranco Family

The Jackson 5

Smokey Robinson

Wes Farrell & David Cassidy

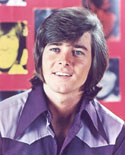

One of the Bahler's recording session contracts. Click on the image for a larger view!

David accepts the Partridges' gold record

Tom in the studio, c. 1972

Michael Jackson's Off The Wall, featuring

"She's Out of My Life"

Frankie Avalon

GH: Let’s back up a bit to Bobby Sherman. You wrote his hit, “Julie, Do You Love Me?”

TB: Right.

GH: Was that written specifically for him?

TB: It was. It was 1969–70. Jackie Mills was his producer and he was an old big band drummer. We knew of Jackie. He is a sweet, sweet man. Lovely man. He hired us and we came in, and it was so much fun! Bobby was this kid on a TV show [“Here Come the Brides”] and nobody knew he sang, either. He was so thrilled we were there. He just couldn’t believe it either.

GH: And you were paid the same way for all this too? One flat fee?

TB: Yeah. We’d come in and get paid “per side” or “per hour”, whichever was more. We would go in and do an entire album in a day. It was a nice chunk of change.

GH: How did you sell them on “Julie, Do You Love Me?”

TB: Jackie Mills came in and said, “It is getting harder and harder to find good songs for Bobby. If you guys know anyone who writes, we are really looking!” My brother told them that I wrote great songs and they should try me. I had never really tried to peddle a song and it scared the crap out of me. But on a break, Jackie asked to hear some of my songs, so I played him a few. They were always about girls. He liked them but didn’t think they were right for Bobby. He asked me to write a few for him, so I tried.

GH: And who was “Julie”?

TB: Julie was a girl I adored so much in high school that I couldn’t even talk to her. I had the biggest crush on her but she was not available. And I was too chicken if she was! So I wrote it about that reminiscence. I wrote it basically as if we were sweethearts.

GH: Did she ever know you wrote it about her?

TB: Yes, years later, at a class reunion, I told her that I had written it for her, and she was just flabbergasted. Since then we have become very close friends and I gave her my gold record a few months ago. She was really moved to tears. It was very sweet.

GH: How many songs did you write?

TB: I wrote about six songs. I spewed out a lot of ideas, but settled on six. I was going skiing with a buddy in Europe and gave the tape to my brother to give to them. I said “If they don’t like these songs, YOU wrote them!” So I called John when I was in Austria, sitting in a bar all juiced up. I asked him what was going on and he said “You’re Bobby’s next single!! Get your ass home, we’re going to record it next week!” I came home, and we recorded it.

GH: So you and John are singing backup on that too?

TB: Absolutely! We are on every one of Bobby’s records. He never recorded without us. We worked with The DeFranco Family then, too.

GH: Did you two always work as a team?

TB: Not necessarily. We were a team when we wanted to be or when others wanted us to be, but we also worked independently all the time. John and I are very close; I can’t imagine having a better brother. We were basically interchangeable. People would say, “get me one of the Bahler brothers!” They didn’t care which one.

GH: What else were you doing at the time?

TB: We did a lot of the arranging for Motown when they came out here in 1972, because they were looking for “black” arrangers. John and I were “black” arrangers, even thought we were white, because we were raised in a black gospel church. So we did a lot of the vocal arrangements for the Jackson 5ive and Smokey Robinson and the Miracles. I used to be over there 2 – 3 times a week. We made a lot of money working over there. It was great.

This is why we didn’t want to be under contract. We were making too much money doing other things. If you are under contract, that’s a bane in our business because then nobody else would use you. Even though we didn’t have a written contract to return as the Partridge Family for every album, they weren’t going to fool with success. In fact, I can’t be sure, but it’s possible that there may have been another guy on there at certain times, if John or Ron or I couldn’t make it. That may not be the case, but it wouldn’t surprise me if it were.

GH: Would Stan Farber have returned for those sessions?

TB: He could have because he was a great singer. If one of us couldn’t make a session, Stan was called to fill in.

GH: David came in, having never recorded before. Did you help him at all? Did you record your background vocals at the same time?

TB: No, we did them after he did his. He would go in when they had the rythym date. He would sing a rough scratch vocal.

GH: What is a scratch vocal?

TB: When the rhythm section is recording their tracks they sometimes prefer to have somebody singing because then they would understand what the song is about. Otherwise it’s just a bunch of chords on a sheet. David would sing and then my brother would get a tape of the rhythm track with David singing, and he’d write the voices to it. We were never in the recording studio when he was. Then Mike Melvoin, who was the music director, would go home and write strings and horns to it.

GH: In order to get the timing of the song correct, did Wes record a scratch vocal for David to listen to?

TB: No, not Wes. Wes couldn’t carry a tune in a bucket. I used to laugh at him. He was terrible! Brilliant guy, but it’s like, I’m not a good football player, but I love it. He wasn’t a good singer, but he loved it.

GH: Was there any kind of vocal guide created for David?

TB: I don’t recall, but Stan and I used to sing lead on the stuff before David, so if there was a vocal for him to follow, it was either me or Stan. Or it could have been Tony Romeo, who wrote some of the songs. That’s a common practice.

GH: You recorded over a half dozen songs before David was brought in. Many are performed on the first season’s episodes, and a few even made it on to The Partridge Family Album. Why didn’t you go back in and add David’s lead?

TB: I think the songs were probably complete as they were. Wes could have felt they sounded fine as they were. Or they were already finished mixing them down to 2 tracks. To go back in and open them up and rework them would have been an awful lot of money. One thing they didn’t do is waste time or money. If it wasn’t going to be a single, what the hell? Why change it?

GH: David has been quite vocal in his dislike for how his vocals were recorded. He claims the earlier records were recorded slower, and sped up to make his voice seem higher. Can you shed any light on why that was done?

TB: That was something that was commonly done in the industry at the time. It wasn’t anything that was done to David’s voice specifically. We have things in the industry known as “Ear Candy”. This is a phrase that I first heard while working with Quincy Jones. It’s something that is a little different in the sound that isn’t enough to be noticed right off the bat.

GH: How was it done?

TB: A number of different ways. They used to wrap the capstans. That’s the thing that runs the tape through. It drives the tape. It would slow down the rotation of the tape. They also used to use a slap reverb, which meant the signal was being run through another machine. It would cause a time lapse. If you listen to Buddy Holly records, that’s what was used there. It was part of the gimmick. In every generation of music, there is always a gimmick.

GH: Was anything like that done to the background vocals?

TB: We used to double-track [record the same part twice], and sometimes we would double them at a different speed. All it does is change the vibrations. When you double track, it doesn’t add more people. If you double a group of four, it doesn’t become eight because it’s the same group of people. It just creates a phasing between the two tracks which gives you another piece of ear candy. When we worked with Michael Jackson, he used to do four tracks of vocals. I worked with him recently. He and I did 42 tracks – just the two of us. We didn’t do it because we didn’t want to hire a choir, we did it because that is the sound he wanted. So, those are things you do for reasons of sound choice. The thing is, David at that time was not experienced in the studio. He was a young man and didn’t understand the ins and outs of pop recording.

GH: These kinds of tricks have been part of the industry for a long time, then?

TB: Sure, and for musicians as well. I wrote “She’s Out of My Life”, which Michael Jackson recorded. When we did the recording, Quincy [Jones] loved the way I played piano on the song when I wrote it, not because I am a good pianist but because there was a certain feeling there. But I couldn’t play it in the key that Michael sang it in. I wrote it in E flat and he sang it in E. I tried as best I could, but it took on a whole other meaning because I am not a pianist and it was just screwed up. We even tried “VSO-ing" [using a Variable Speed Oscillator] it up a half step, but it didn’t feel right. So, Quincy recorded me playing it in my key and we made a tape for the pianist who was going to record it for the album. He took it home and studied it in order to grasp whatever magic was there in my performance. When I listen to the record, I think, “God – it sounds just like me!” Those are called “polaroids” in making records. You do polaroid vocals, too.

GH: Did you do polaroid vocals for any other performers at the time?

TB: When I was working with Jackie Mills on Bobby Sherman’s stuff, he was also working with Frankie Avalon on an album that was going to feature my songs. I’m not sure if it ever came out, I don’t remember, but Jackie had me sing every song for Frankie and Frankie would listen to my vocals in the earphones while he was singing.

GH: Is that because he wanted Frankie Avalon to sound like you?

TB: No, not necessarily. It’s worth a thousand words. Especially since most artists don’t read music because it’s not important. If they do read it’s like looking at a blueprint. You can’t get the feeling from the blueprint. For instance, when Paul McCartney and Michael Jackson sang “Say Say Say”, Michael laid down the vocals. Paul came in and sang to Michael’s vocals in the earphones. But at some point, he said, “OK, take him out, I’ve been guided long enough.” During the Partridge years we were in a studio that was, and still is, one of the best studios in town – Western 2. It was an expensive studio. When you’re in there, time is at a premium, so you don’t want to be spinning your wheels, trying to learn something. So the long and short of it is it was common practice. You know why? Because at the time, VSO-ing just came in. It was a toy.